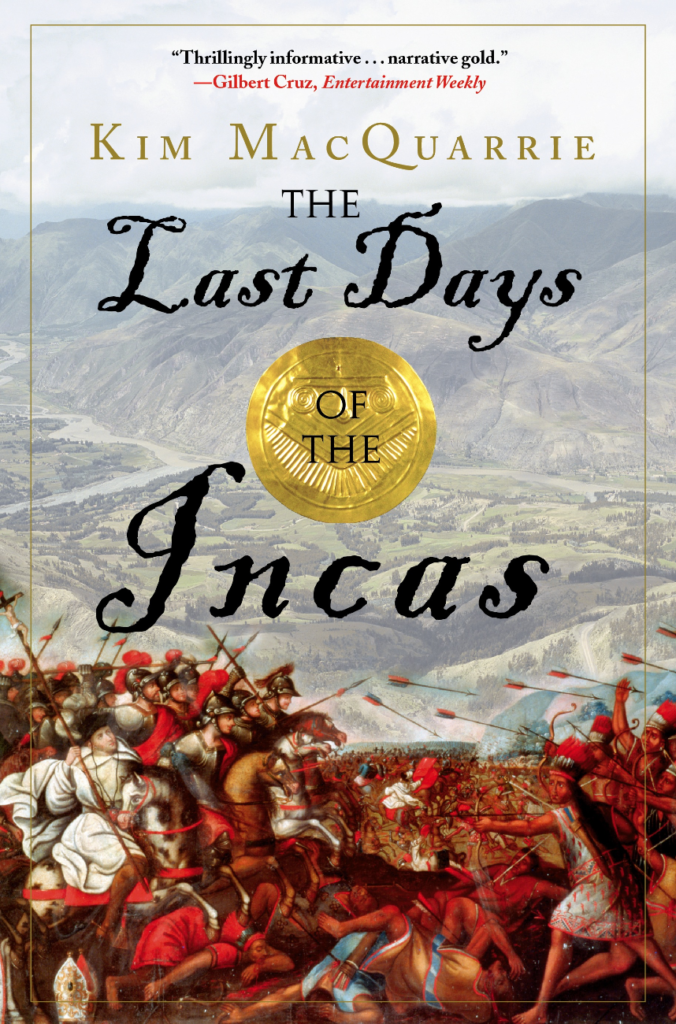

The Last Days of the Incas

Between 1200-1230CE, a small tribe in the Andean highlands settled and began a new city-state named Cusco. By 1532, this tribe, the Inca, had assembled the largest empire in the western hemisphere, encompassing 770,000 square miles of territory. And, amazingly, they achieved this without the wheel or animals to ride or plow. Without iron or knowledge of writing. The Inca built an empire featuring monumental stonework and architecture, with an intricate road system spanning their lands.

Lacking writing, they developed a way to use knotted strings to keep amazingly accurate records and facilitate communication. The Inca overcame handicaps in arable land, with advances in agriculture, and were incredibly efficient in the management of resources and personnel. On top of it all, they had no money, the economy was based on bartering and exchanging of goods and services.

Inca also did not have was a tradition of a peaceful succession of power when the emperor died. To be fair, the Old World was hardly better at this tradition, but the Inca expected for succession to plunge the empire into civil war. The best and strongest claimant to the throne would win, and lead the empire going forward. It had been this way for nearly 300 years.

Between 1527 and early 1532, the Inca Empire had been locked in just such a struggle. Huascar and Atahualpa, two brothers of the previous emperor, waged war on each other, and by May 1532, Atahualpa was on the cusp of victory and crowned emperor. Huascar’s forces were scattered, and only his last stronghold at the capitol Cusco remained. As Atahualpa’s generals planned for the final siege, the new emperor retired to the royal thermal springs at Cajamarca, in order to fast and pray for success. On November 15, 1532 word came to Atahualpa that Huascar was dead, Cusco was captured, and the empire was wholly and completely his.

The emperor’s opportunity to savor his victory would be unbelievably short lived.

On the very day messengers delivered the news to Atahualpa of his victory, a man from Spain named Francisco Pizarro was climbing the Andes from the coast, and mere miles away from Cajamarca and the Incan emperor.

Arriving with 168 men at his command – 106 infantry, 62 cavalry and 1 cannon, Pizarro’s luck was the opposite of Ataphalpa’s. Within 48 hours, Francisco Pizarro had captured the Inca emperor and unleashed a surprise attack that massacred 2,000 or more Inca while driving the rest into the countryside. Over the next 40 years the Inca struggled to throw back the Spanish. And, over the time they came so tantalizing close, but, ultimately, it was not to be.

Kim MacQuarry’s “The Last Days of the Incas” is a detailed and in depth study of conquest of the Inca Empire, and I would encourage any interested in the period, or Inca/Peruvian history, to check it out.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts